🧠Understanding the 6 Stages of Crisis🌋

The first you usually know about a crisis is when a child throws something across the classroom. Read this post to understand how they got there.

👋 Welcome to SEMH Education!

Every week, I share insights, strategies, and tips from my experience working with children and professionals on social, emotional, and mental health in education. This week, we’re exploring a model used in many educational settings: The 6 Stages of Crisis Model. I’ll go through each stage and highlight my own experience with it, sharing my top-tips as we go!

Let me know you’re here! Clicking the ♥️ button or pressing the ‘L’ key on your keyboard shows me you’re here and enjoying my content 😊.

6️⃣ Stages of Crisis

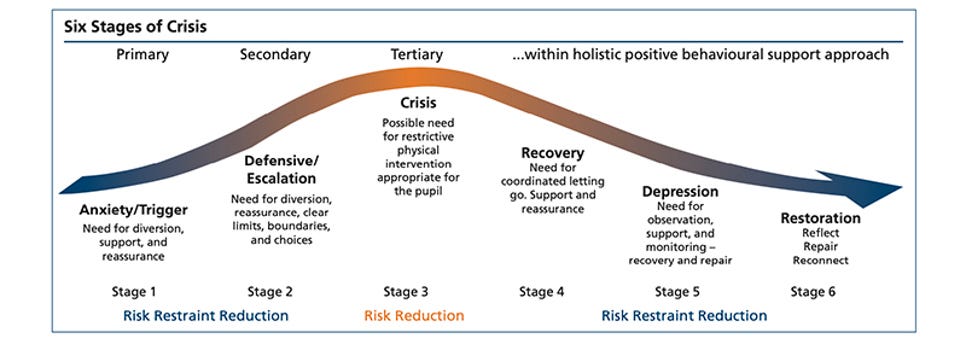

In schools, crisis behaviours such as throwing items across a classroom, unpleasant verbal language and physical altercations - usually the result of emotional dysregulation and/or extreme distress - are something educators must now be able to navigate. Understanding the 6 Stages of Crisis can help school staff respond proactively, reduce harm, and support recovery.

This model is widely used in educational settings, I’m sure some of you have come across it before. I would like to go through each stage and outline my own experiences of children in these stages, coupled with techniques I’ve used. All of which will be backed by research from Educational Psychologists (EPs) and other sources.

Image from: Headteacher Update

1. Anxiety / Trigger 😟

This first phase can often go unnoticed. You have to really know the children in your class to be able to identify when they may have entered stage one. However, this is the most important stage. If you can successfully support a child at this stage, they are less likely to enter crisis.

🔍 What it looks like:

The student shows early signs of distress (e.g., fidgeting, avoiding work, or withdrawal).

May become irritable, restless, or seem overly sensitive.

External or internal triggers (e.g., sensory overload, frustration, or social conflict) initiate the distress.

✅ How to support:

✔️ Early intervention is key. Acknowledging their feelings before escalation is critical. This can be a simple sentence such as; “This work is really difficult, I’m not surprised you’re finding it frustrating.”

✔️ Offer reassurance, structure, and predictability (e.g., “I can see you’re finding this tricky, let’s take a moment.”).

✔️ Reduce sensory triggers where possible (dim lights, reduce noise).

🧑🏫Own Experience: Create a trigger list within your staff team. Once you get to know each child you’ll begin to understand what their stage 1 trigger is. Put this next to the class register along with a technique that helps them. For example:

Joe Blogs - tapping pencil & feet - give job & offer support.

In this example, Joe’s behaviour to let you know they’re in stage 1 is when they begin tapping their pencil and feet. You know Joe likes to be given jobs in the classroom so when you spot this behaviour you ask Joe if he can help you with handing out the rest of the rest of the books (or any other impromptu job). Whilst completing the job with Joe you ask if he’s feeling okay and if he’d like any support completing the first task of the lesson.

An alternate way to phrase this for pupils you know might refuse the offer for support could be as follows: “Thank you for helping hand out the books, you were great! Can I come and work out the first task with you? I’ve forgotten the answer myself and I bet we’d be able to work it out together easily!”

🔎 EP Insight: Educational psychologists emphasise proactive strategies at this stage as children are most responsive to preventative regulation techniques (Shanker, 2016).

2. Defensive / Escalation 🎢

This is the stage right before crisis and your last chance to prevent the child from displaying crisis-level behaviour. There are a couple of things to note at this stage. I would allow the child more time to regulate when they’re on the verge of crisis rather than stage 1.

In specialist settings this may mean the child needs to regulate for the remainder of the day. This is okay and is less damaging than tipping the child into crisis.

I would still complete stage 6 with a child who has entered stage 2. Any behaviours outlined below warrant a discussion and reflection with the child, as they are unacceptable for most classroom environments and cannot be seen to be allowed.

🔍 What it looks like:

Increased agitation: raised voice, refusal, verbal outbursts, pacing, clenched fists.

May challenge staff, argue, or show controlling behaviour.

Logical reasoning begins to decline.

✅ How to support:

✔️ Stay calm and maintain clear boundaries, avoid power struggles and arguing.

✔️ Give limited choices: (“Would you like to take a break in the sensory area or some time outside?”).

✔️ Keep instructions short and avoid emotional reactions. In this stage, the goal is to prevent further escalation.

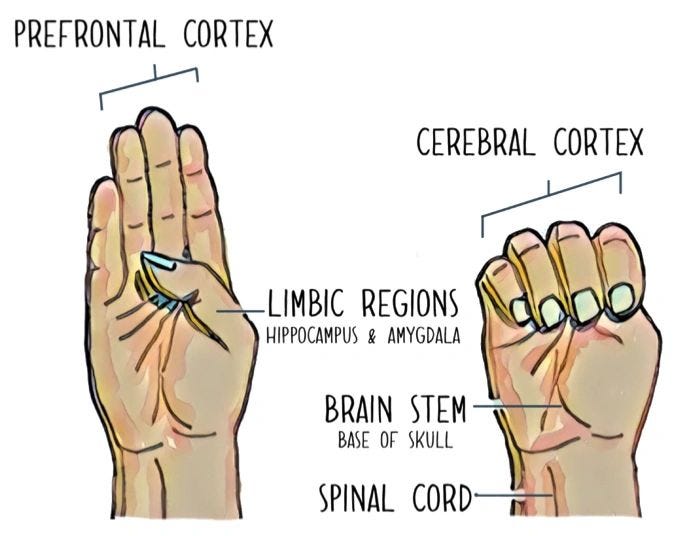

🧑🏫Own Experience: Two things that work really well for stage 2 are concise options and simple language. I’m talking 1 or 2 words. For children in stage 2, their brain is entering fight, flight or freeze mode which switches off their rational brain (Amygdala).

What’s worked for me really well in the past is offering choices to regulate in one-word answers such as “Outside?” or “Lego?” The child will often not answer verbally to these but start walking towards the door to go outside or cupboard where the Lego is kept.

If children look like they are just ‘shutting down’ E.G. remaining in one place, not talking or making eye contact. I would always opt for mirroring their body language. I’ve found this works really well and can provide a sense of connection and safety.

🔎 EP Insight: Research shows that co-regulation from a calm adult significantly reduces the likelihood of reaching crisis (Porges, 2011).

3. Crisis 🌋

Crisis behaviours can be scary and traumatic for all involved. It’s important to put your own mental health first and take a break if you need to. Having a child and adult in crisis will result in the behaviour continuing for longer than necessary. It’s important to maintain your own regulation and swap out with another adult whenever necessary.

🔍 What it looks like:

Full emotional overwhelm - shouting, aggression, harm to themselves and/or others, or complete shutdown.

The fight-flight-freeze response is dominant.

Rational thinking is offline now, no reasoning is that effective.

✅ How to support:

✔️ Prioritise safety, this may include removing others if needed and minimising interaction.

✔️ Use non-verbal de-escalation—slow movements, open body language.

✔️ Avoid threats or lectures to the child. Simply be present and available when they’re ready.

🧑🏫Own Experience: I’ve had my fair share of crisis incidents in my classroom, especially in the specialist SEMH settings I’ve taught in (see image below). Crisis situations are extremely challenging, they’re mentally draining and physically exhausting.

However, there are two things which I’d say are essential to navigating a pupil and/or whole class through crisis - yes, in specialist settings you will sometimes have 6+ pupils all in crisis at the same time. It’s like dominoes, once one slips into crisis, the others go as well!

Staying Calm - This is really tricky, sometimes children’s behaviour is shocking and a natural way to respond to this is by increasing our volume (shouting), showing disapproval or reacting in a knee-jerk fashion. In my experience, this only fuels the fire and increases the level of behaviour from the child as they continue to feel unsafe and threatened.

As long as the child and/or others are not at immediate risk of harm, staying calm is the most powerful and effective way to guide a child out of crisis. Using your normal voice, offer simple 1 or 2-word instructions. Make sure your body language is as neutral as possible - don’t go waving your arms around!

Ask for support: If you’re fortunate enough to have radios in your school then radio for extra support whenever necessary - Ideally once you’ve began to regulate the pupils and you’re in need of some time out yourself!

🔎 EP Insight: Physical intervention should always be a last resort, used only when safety is at risk. Research highlights the importance of trauma-informed de-escalation techniques over restraint (van der Kolk, 2014).

The image below is a great way to simply explain what is happening in the brain when children enter crisis.

Image from: LearnForLife Blog Post

4. Recovery ❤️🩹

You’re not out of the woods yet in this stage. It’s extremely easy to go from crisis to recovery and back again. I’ve seen this play out many times! It’s important during this stage that pupils and staff are offering low-threat options and communication to develop a feeling of safety and security.

🔍 What it looks like:

The child starts to calm down, their breathing slows, and their body relaxes.

They may be tired, teary, or embarrassed.

Still emotionally fragile and prone to re-escalation if pushed too soon.

✅ How to support:

✔️ Allow quiet recovery time with no pressure to resume the lesson.

✔️ Offer low-demand reassurance (e.g., a cup of water, time in a safe space).

✔️ Avoid over-talking, keep your communication simple and calm.

🧑🏫Own Experience: This is a key phase within the stages of crisis. If you attempt to leave this stage too early then the child could easily re-enter crisis. My top tip for this stage is to allow plenty of time for the children to regulate and ensure that you regulate yourself!

Regulate yourself: My go-to after a crisis incident was to have some of the class watching videos on YouTube and some others playing football outside. I’d then take turns with my Teaching assistants and other staff to have a 5-minute break and a cup of tea. This allowed the children around 15-20 minutes to regulate themselves and the staff time to regulate too. It is almost impossible to go from a crisis incident and regulate the pupils to the next lesson without regulating yourself.

🔎 EP Insight: Studies show that children need space to regulate before re-engaging. Immediate problem-solving can lead to re-escalation if done too soon (Perry, 2006).

5. Depression 😔

🔍 What it looks like:

The student may feel guilt, shame, or exhaustion.

They might withdraw, avoid eye contact, or appear unusually quiet.

Can be mistaken for regulation, but emotions are still fragile.

✅ How to support:

✔️ Observe without overwhelming, be available but not intrusive.

✔️ Encourage small steps toward re-engagement (e.g., simple tasks).

✔️ Offer a structured check-in: “Do you want to talk now, or later?”

🧑🏫Own Experience: In my experience, this stage often happens a significant time after the crisis period. Sometimes it lasts over the course of hours and days. It’s important to keep checking in with the child throughout this period. It’s often too soon for them to talk about the incident but make sure the child knows you’re there to support them.

It’s okay at this stage to offer other activities in an attempt to re-engage the child with their learning. This stage can last the remainder of the day and sometimes multiple days.

It’s acceptable to stay in this stage for as long as needed. However, it is critical that you complete stage 6 once the child is ready. Otherwise, the child may think there are no consequences for their behaviour and will not fully understand the impact their behaviour had on others.

🔎 EP Insight: Emotional fatigue after a crisis is common but often overlooked. Providing empathetic, non-judgmental support is key Pfefferbaum, B., & North, C. S. (2020).

6. Restoration 🏗️

Without this stage, children are unable to understand how their actions made others feels. It’s a key stage to unpick what caused the initial crisis and can rebuild bridges with staff and other pupils.

Without this stage, you are at risk of the child losing friendships and slowly becoming isolated within their class, year group or entire school.

🔍 What it looks like:

The student is ready to reconnect and reflect.

May be open to problem-solving and discussing what happened.

Emotional regulation is restored.

✅ How to support:

✔️ Use restorative conversations: “What helped? What can we do differently next time?”

✔️ Focus on learning, not punishment, consequences should be logical, not punitive.

✔️ Rebuild trust, reminding them that one crisis does not define them.

🧑🏫Own Experience: I find this the easiest stage and the one I actually look forward to. It often gives you insights you didn’t have before which enables you to prevent further crises from taking place.

I’ve previously written about how to rebuild trust after a crisis and the 4 questions I use to facilitate restorative conversations between peers, so I won’t go into them in-depth here.

Top tips for this stage is to have those restorative conversations as soon as all parties are ready and able. Prolonging this just leaves and air of awkwardness and feelings of anxiety. It’s best to talk about the incident and move on in a productive and agreeable way.

🔎 EP Insight: Reflective conversations strengthen emotional intelligence. Research shows that when students feel supported rather than shamed, they develop stronger self-regulation skills (Stanley, 2017).

🤔 Final Thoughts: Early Intervention

The Six Stages of Crisis model is not just about managing difficult moments. It’s about teaching long-term emotional regulation. By recognising early signs of distress and responding proactively, educators can reduce crisis moments and build resilience in CYP.

Key Takeaways:

✅ The earlier we intervene, the less likely crisis becomes.

✅ Co-regulation is essential, students mirror our emotional state.

✅ Restoration is just as important as de-escalation. Repairing relationships after a crisis is essential.

I would love to hear your experiences, how does your school support students through crisis? Drop a comment below!

This was very informative. I was intrigued by this article as I am CPI certified. It brought a ton of value so thank you. Many teachers at my school need training in this area. I try to teach them how to recognize (warning signs) potential crisis and how to deescalate when it happens. In my experiences, I have learned that students can go through these stages in a short amount of time when there is a heated verbal altercation that may lead to a potential physical altercation. I am new to Substack but I plan on putting valuable information out. Thanks for the story.

This is such a helpful post! I particularly like the image of the hand when describing a child in crisis. I call it blowing one’s top when the limbic regions are exposed due to crisis.